A year ago, Myanmar’s faltering transition to democracy was halted in its tracks and, arguably, the future of the country as a modern state was put on hold.

In the early hours of February 1, 2021, the military arrested senior members of the democratic movement, which had won a landslide victory, as they prepared to enter parliament to form a new government.

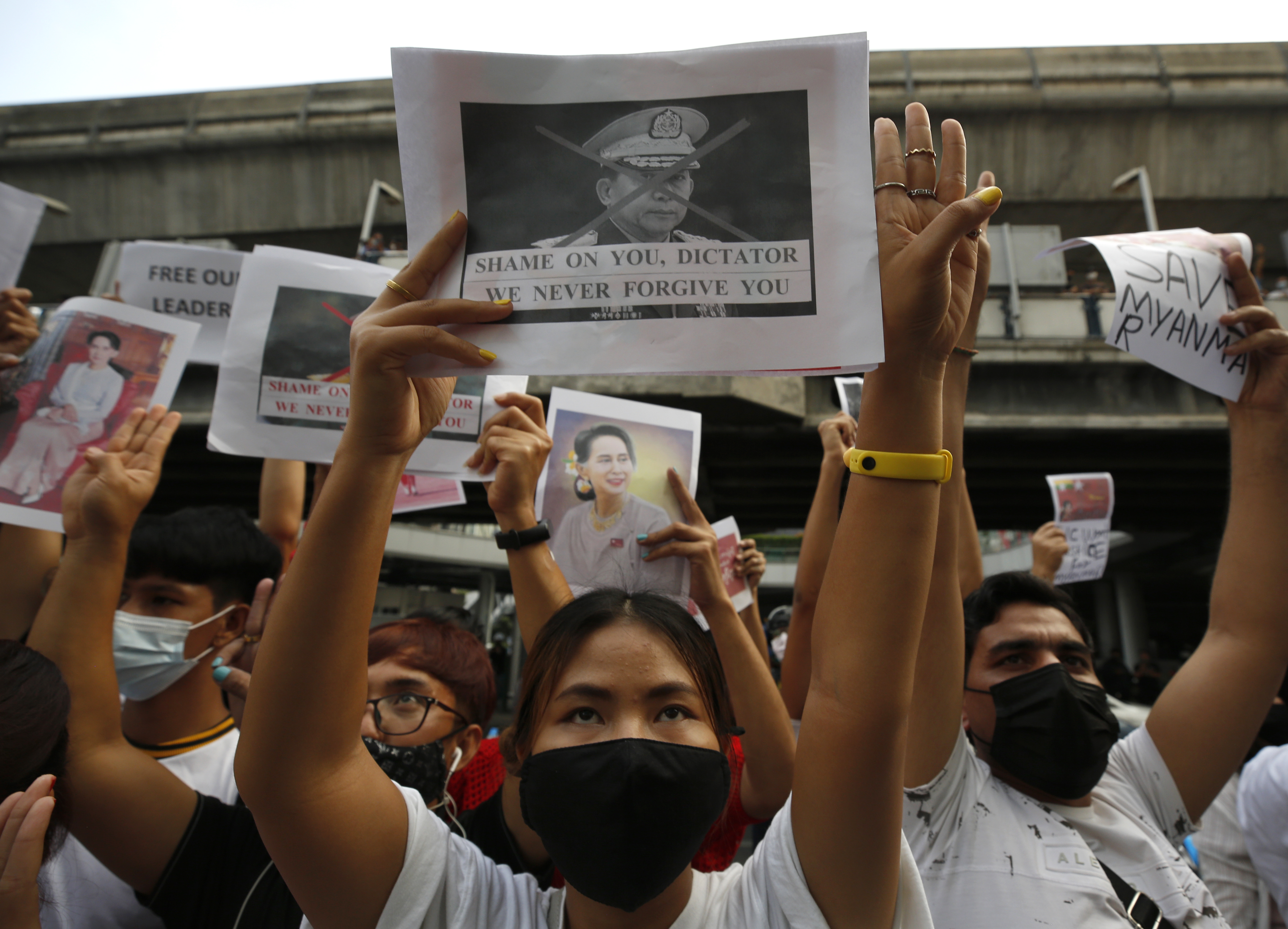

Inspired by the courage of a new generation, a techno-savvy protest movement was born in a matter of hours, as millions rose up across the country in a sustained campaign to reject military rule. This was the 1988 democracy uprising gone digital.

But as in ‘88 the cruelty of the generals knew no limits.

Coup leader Min Aung Hlaing unleashed an industrial-scale campaign of state terror and collective punishment that surpassed that which was seen in 1988, with massacres, indiscriminate aerial bombardments, widespread arson attacks, mass arrests, forced labour and disappearances.

The number of people displaced has risen to over half a million, including tens of thousands who have fled across borders to neighbouring India and Thailand.

Crimes against individuals have proliferated exponentially. Some 1,500 people have killed by the junta since the coup—many tortured to death in prison—and nearly 9,000 are in junta detention centres, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners.

State violence has crossed the threshold of crimes against humanity and war crimes, as defined by the Rome Statute which established the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Since the coup, the Myanmar air force has carried out indiscriminate airstrikes on civilian areas in at least 26 townships, according to a mid-January update from the National Unity Government.

From February 1 until the end of 2021, there were 7,686 clashes and attacks on civilians in the country, a 715 percent increase from the same period in 2020, according to the advocacy groups Progressive Voice and ALTSEAN.

This sets Myanmar on a par with the most brutal conflicts of our times, comparable over the same period with Syria (7,742), and higher than Afghanistan (6,481), Yemen (6,270), and Iraq (3,732).

In the last four months of 2021, Myanmar has overtaken all of these.

Since October 2021, there has been a marked—and well documented—escalation in the junta’s war against ethnic armed organisations and ethnic communities; whole villages have been shelled and torched. Civilian targets such as churches, schools and hospitals have been routinely hit.

Health officials and humanitarian aid workers have been killed, including two Save the Children staff members in the now infamous Christmas Eve massacre in which the bodies of more than 40 people were found bound, gagged and burnt in Karenni State.

According to the World Health Organisation, there have been 286 attacks on Myanmar’s health care system since the coup; this figure constitutes more than one-third of all such incidents reported worldwide over the same period.

The global community’s response is an international disgrace.

A neutered UN Security Council, has taken no meaningful action and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations—ASEAN—has been ineffective to the point of virtual complicity in the crimes of the junta.

So what must change?

Accountability must be put front and centre, beginning with a referral to the International Criminal Court (ICC) by the UN Security Council.

If Russia and China threaten to veto, let them. Other Security Council members such as the UK and the US must then call out this negation of the Council’s responsibilities as mandated by the UN Charter.

In the absence of a Security Council referral, the ICC must initiate action and investigate the junta. Our organisation, the Myanmar Accountability Project (MAP), has submitted a criminal file to the Court against Min Aung Hlaing for crimes against humanity. Exhaustive evidence available to the ICC from the Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar would likely see a conviction.

There must also be an enforced global arms embargo against Myanmar by the UN. And again, it’s time for member states to name and shame the violators.

There must be increased criminal prosecutions brought under universal jurisdiction which—as shown with a recent case in Germany relating to Syria—can be a powerful tool for enforcing accountability.

MAP will soon be submitting cases to courts in Istanbul and Jakarta to convict Myanmar junta officials. There must be more.

Interpol must step up to the plate and apprehend perpetrators.

International organisations must speak out when junta representatives attempt to join them. MAP will soon launch a “Junk the Junta” campaign to this end and as a constant reminder to the world that the dignity and destiny of the people of Myanmar must not be forgotten.

The UN General Assembly decided unanimously last December to reject the credentials of the junta. We must build on this. Min Aung Hlaing must be denied the recognition he craves.

The National Unity Government which enjoys the overwhelming support of the Myanmar people, must be recognised by UN member states, who voted overwhelmingly for the restoration of democracy in a General Assembly resolution in June 2021.

In consultation with ASEAN and key regional powers such as Japan, the UN as a whole, led by the Secretary General, must formulate a cohesive and comprehensive roadmap, based on political, diplomatic and humanitarian pillars.

The UN country team in Myanmar, which has been dogged by a lack of leadership and coordination, must engage meaningfully to support civil society organisations working courageously across the country.

All of these suggestions are politically and practically feasible. We must all seize the opportunity and set Myanmar on a new path.

After the 1988 revolution was crushed, Myanmar was forgotten for two decades.

We cannot and will not allow history to repeat itself.

Chris Gunness covered the 8888 uprising for the BBC and is now Director of the Myanmar Accountability Project, where Damian Lilly is the Director of Protection.