One year after declaring a “resistance war” against the coup regime that seized power in February 2021, Duwa Lashi La, the acting president of Myanmar’s shadow National Unity Government (NUG), knows that it is still too soon to say that victory is within reach.

Although the NUG says that the resistance has deprived the junta led by armed forces chief Min Aung Hlaing of control over much of the country, its ultimate goal—of ending military rule once and for all—will only be reached when it has overcome a number of serious hurdles, he says.

While a huge disparity in firepower remains one obvious challenge, another is the need to transform the many groups opposed to the regime into a more cohesive fighting force. In a recent interview with Myanmar Now, the NUG president stressed the importance of both funding and training. Finding the financial means to properly equip those fighting on the frontlines has been a major priority of the NUG, he said, but it is not the only one. Another is providing young volunteers with training that doesn’t just make them combat-ready, but also deepens their familiarity with codes of conduct and chains of command.

But properly armed—with both weapons and military discipline—the NUG’s People’s Defence Force (PDF) and its many allies will ultimately prevail, he insisted.

We had no choice but to respond with the language they understand by disciplining them with weapons. Since weapons are the only thing they care about, I believe this is the only way of resolving the problem we are facing – Acting president Duwa Lashi La

Regarding the decision to take up arms against the regime, after decades of resisting its predecessors by more peaceful means, he said that the junta’s brutal efforts to establish its rule had made it unavoidable.

“We had no choice but to respond with the language they understand by disciplining them with weapons. Since weapons are the only thing they care about, I believe this is the only way of resolving the problem we are facing,” he said.

The role of EAOs

Another key to success will be strengthening and expanding alliances between newly formed armed groups and those that have fought Myanmar’s military rulers for decades. Ethnic armed organisations (EAOs) have played a key role in sustaining the ongoing fight against the regime, and will continue to do so as the armed resistance movement enters its next phase, which is offensive war, according to the NUG’s defence minister, Yee Mon.

Up until this point, most engagements with junta troops have been defensive operations or ambushes aimed at disrupting the military’s ability to send supplies and reinforcements into conflict areas. Such actions have done little to fundamentally undermine the military’s hold on power. Now, however, the NUG believes that it is ready to mount more direct attacks on the junta’s command structure, Yee Mon told Myanmar Now in a recent interview.

With the help of EAOs—including some that have only recently begun to cooperate with the NUG—the resistance will soon be able to mount military offensives that will not only liberate more territory, but also seriously weaken the regime, he said.

In a panel discussion held to mark the first anniversary of the start of the resistance war against Myanmar’s military, Yee Mon described the PDF as “a force that the junta is unable to crush,” thanks to both the EAOs and the public, which he said has been steadfast in its support.

Anthony Davis, a regional security and military affairs analyst who took part in the same discussion, concurred that the achievements of the resistance forces to date have been “truly remarkable.” He credited this largely to the courage of the Myanmar people, but also noted that EAOs—or ethnic resistance organisations (EROs), as they are also called—have had a tremendous impact.

“It’s important to remember that the areas where the resistance has caused the military the most damage, has inflicted the heaviest casualties on the military, have been precisely those areas where PDFs have been able to benefit from the experience on the battlefields of EROs,” he said.

The NUG, which has declined to identify each EAO ally by name, says it has worked closely with eight groups so far. Some, such as the Karen National Union (KNU) in the south, the Kachin Independence Army in the north, the Chin National Front (CNF) in the northwest, and the Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP) in the east, have openly provided military training and other forms of support. They have also fought alongside PDF forces in joint operations, in many cases with their own officers embedded in newly formed units to act as frontline commanders.

According to Davis, the regime is well aware of the danger that this situation poses to its survival. Such alliances are “a critical threat” to the junta that it will seek to break by any means possible, he said, pointing to its repeated efforts to engage in “peace talks” with individual EAOs in recent months as one part of this strategy.

The regime even seems to fear that the United Wa State Army (UWSA), the country’s largest and strongest EAO, could eventually end up tipping the balance in favour of the resistance. At a meeting held in late May, it agreed in principle to the Chinese-backed group’s demand that the Wa region be upgraded to a “self-administered state.” This appeared to have the desired effect: In remarks made after the meeting, UWSA leaders called the post-coup crisis an “internal affair” of the country’s ethnic Bamar majority and vowed not to take sides in the conflict.

The Arakan Army (AA), another EAO that has said it wouldn’t get involved in the “Spring Revolution” that erupted in the wake of last year’s coup, has nonetheless said that it was a “friend” of any group fighting against oppression. More seriously, however, it has resumed hostilities at a time when the military is already stretched to its limits. As the conflict in Rakhine State continues to heat up, this could have a major impact on the course of the war elsewhere in the country.

‘Starting from nothing’

Even before the NUG formed the PDF in May of last year, tens of thousands of young people had begun volunteering to join the nascent armed resistance movement. This created a vast pool of recruits ready and willing to sacrifice their lives for a cause that continues to enjoy strong popular support.

(Over the past year, some 1,500 resistance fighters, including members of EAOs, have already made the ultimate sacrifice, according to the NUG. Meanwhile, it estimates that more than 20,000 junta troops have lost their lives waging war on those opposed to the regime and ordinary civilians.)

According to NUG Defence Minister Yee Mon, the number of troops currently serving in the PDF is now around 70,000. Figures released by the ministry in May indicate that a year after its formation, the PDF had a total of 300 active battalions and a similar number of township-based People’s Defence Teams (PDTs). While the former operate under military divisional commands, the latter are under the direct control of the Defence Ministry and are tasked with engaging in urban guerrilla warfare, providing training and logistical support, and collaborating with the PDF battalions during major operations.

In addition, there are hundreds of village- and township-based local defence forces (LDFs) operating around the country; while independent of the NUG’s military command, these forces often join in military actions with the PDF and its other allies. The total number of fighters active in these LDFs is believed to be roughly equal to that serving in the PDF.

While these figures would appear to support the NUG’s claims that it has the capacity to mount major offensives against the regime, some involved in the resistance say they are not so certain. They note that the lack of unity among all these disparate forces remains an issue that has yet to be resolved.

“I believe that the strength of our unity will be more decisive than whether we go on the offensive or not,” said Nway Oo, the spokesperson for the Civilian Defence Security Organisation of Myaung, an LDF based in Sagaing Region.

Speaking to Myanmar Now recently, he said that the NUG needs to do more to unify armed groups fighting on its side before it embarks on more ambitious military operations. He added that after a full year of conflict, there are signs that the solidarity that has held the resistance forces together this long is beginning to fray. The NUG must act fast to reverse this trend, he said.

For its part, the NUG appears to be more focussed on the question of how it will arm the troops already under its command. Vastly outgunned by the enemy, it hopes to supply some 20,000 PDF troops with rifles over the next four months, according to Yee Mon. To reach that target, the NUG will have to spend at least $100m, he said.

As a “self-reliant revolution,” the armed resistance movement in Myanmar has had to rely heavily on public support to meet its financial needs. While it is impossible to put an exact price tag on the fight against the regime, NUG member Nay Phone Latt estimated in May that the cost of the conflict was around $10m per month. While much of this has flowed through the NUG, some has also come directly from the public to groups fighting on the ground.

Even if we are not satisfied with what it has accomplished, it is a revolution that started off with nothing and we should recognize and understand that it has overcome many struggles over the past year – KNU’s spokesperson Saw Taw Nee

Also difficult to measure is the actual number of clashes that have taken place. While the KNU has recorded more than 6,000 military engagements in its territory since the coup, other groups, such as the KIA, have remained silent on the total figure in areas under their control in order to maintain operational secrecy.

However one quantifies the scale or cost of the conflict—which has also devastated countless livelihoods in the country—it is clear that it has been far larger than anything the regime anticipated when it decided to overthrow Myanmar’s elected civilian government. Outrage over that act has fuelled an uprising unlike any other the country has ever seen.

“Even if we are not satisfied with what it has accomplished, it is a revolution that started off with nothing and we should recognize and understand that it has overcome many struggles over the past year,” said KNU spokesperson Saw Taw Nee.

Taking the war to an enemy

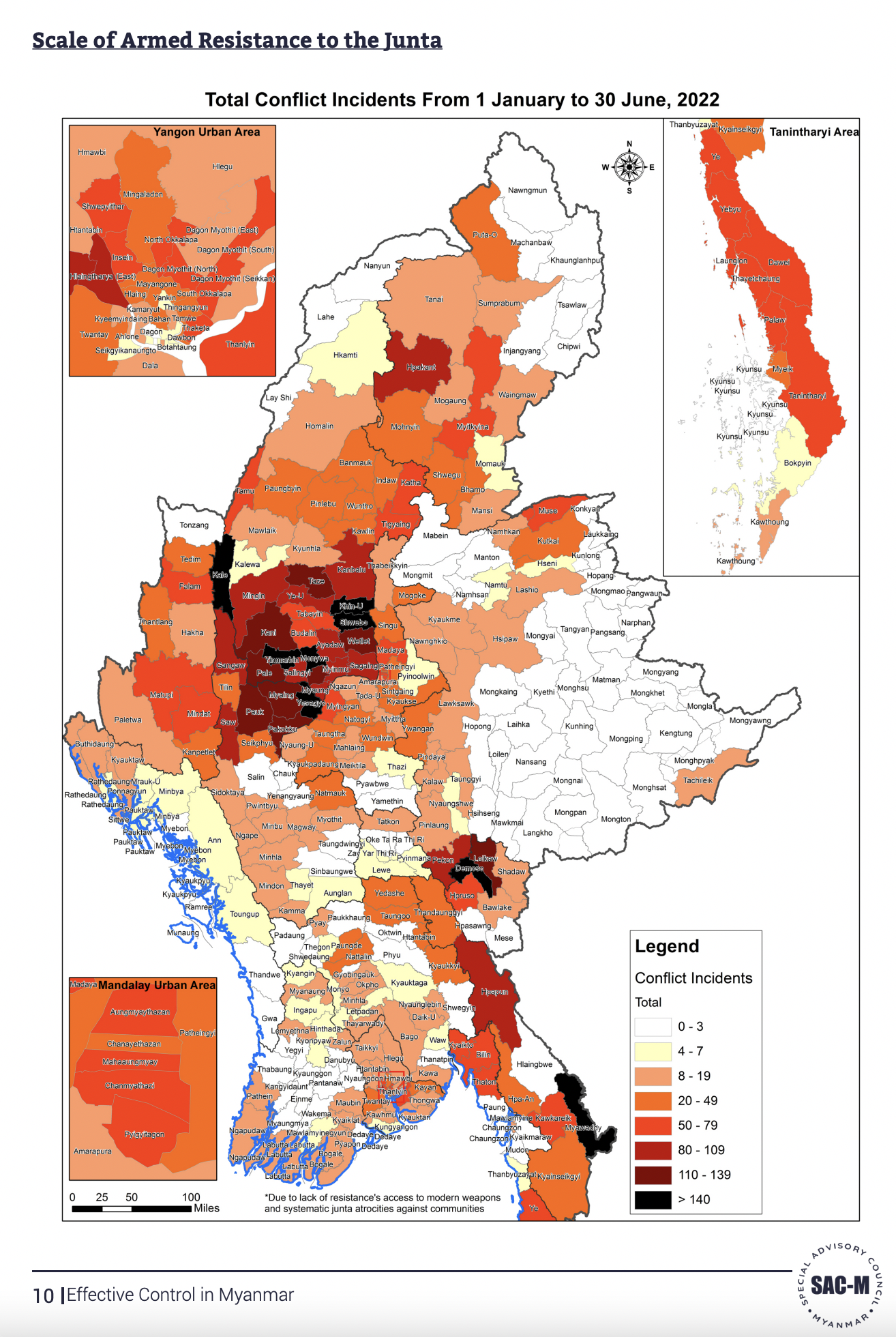

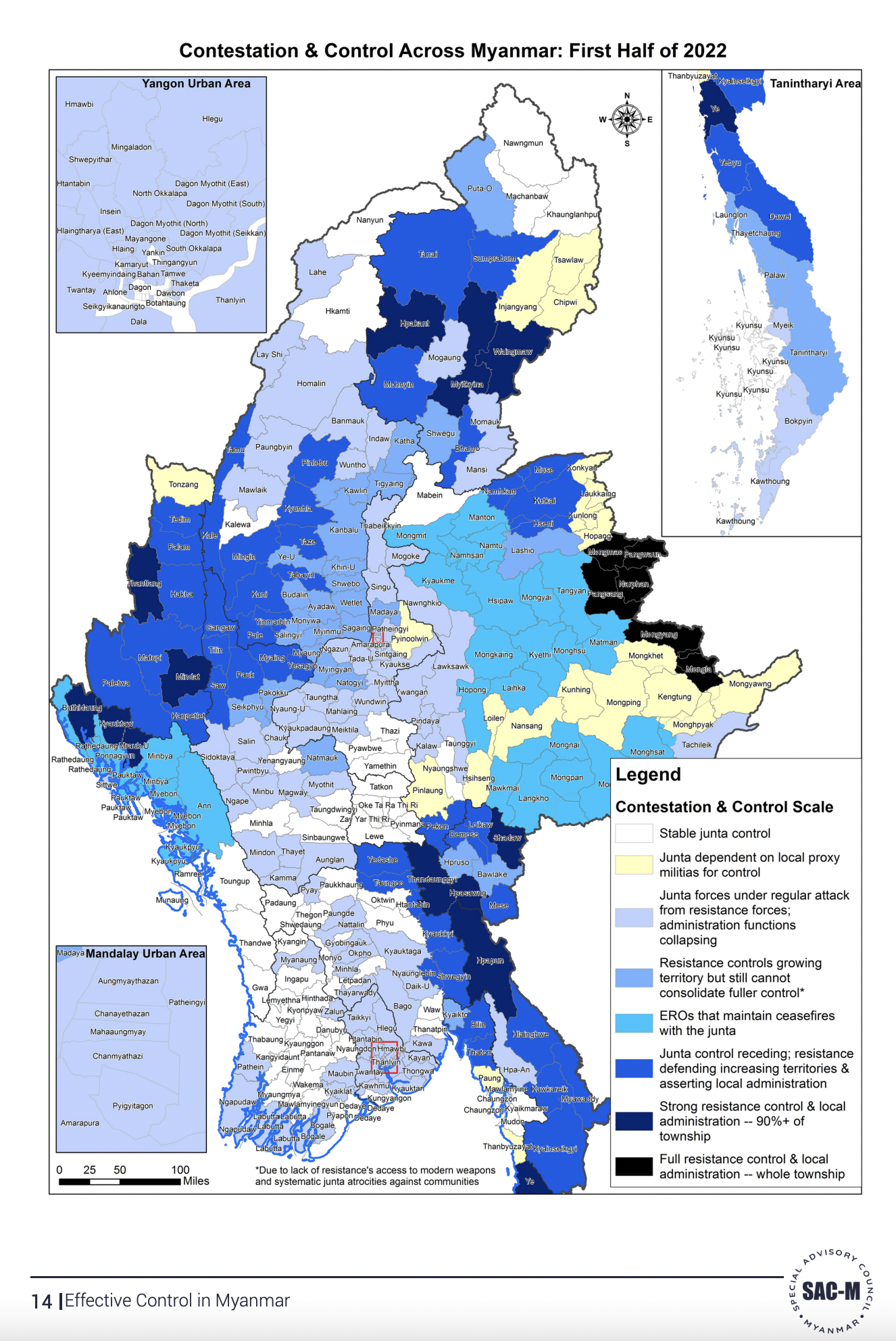

In a report released earlier this month, the Special Advisory Council-Myanmar (SAC-M)—a group of former diplomats and human rights experts monitoring the post-coup situation—confirmed that the NUG and its allies have effective control over 52% of the country’s territory, while the regime has stable control over just 17%, with the remainder being either heavily contested or controlled by EAOs that have maintained ceasefire agreements with the junta.

“The trajectory of the conflict favours the resistance, and the junta is losing what control it does have at an increasing rate despite the continued use of mass atrocities by junta forces,” according to the report.

As badly as its scorched earth tactics have failed, however, the regime has shown no signs of backing down on its use of indiscriminate violence to impose its will on the country. It continues to wipe out entire communities, sending thousands fleeing for their lives as their homes are destroyed. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimates that there are currently around 1.2m displaced civilians in Myanmar—an increase of 800,000 since the military takeover.

According to Saw Taw Nee, around 300,000 of those who have so far been forced to flee their homes live in KNU territory. This was, he said, a harsh reality that groups opposed to military rule have had to accept as a consequence of their decision to engage in armed resistance.

“The dictatorship that we are fighting is one that picks on civilians and targets them whenever they come under fire [from their armed opponents]. It’s a huge problem that we have to do our best to deal with,” he said.

Anthony Davis, the regional security expert, warned that there would likely be more of the same to come. He said that Myanmar’s military has no history of breaking from within, and has always shown itself to be more than willing to resort to extreme violence to hold on to power.

He also highlighted the fact that the resistance seems to be preparing to take its struggle to the next stage, after a year of strategic defence based on small-scale guerrilla operations.

“The second stage is the stage of strategic balance, in which revolutionary forces are able to organise and arm to the point which they can not only maintain their own survival but also develop to carry the war to an enemy, which is being pushed increasingly onto the back foot,” he said.